It’s easy to play armchair quarterback by offering early criticism, so I felt that it was important to withhold any commentary until a majority of the facts came to light.

On October 21, 2021, in New Mexico, on a set for the movie “Rust”, a live round was discharged from a firearm, resulted in the fatal shooting of the cinematographer and injury to the director.

As a result of the incident, key people involved in handling the gun have been scrutinized by the media:

- Alec Baldwin, who was handling the gun at the time of the discharge.

- Hannah Gutierrez-Reed, who was the Weapons Master, also known as the armorer, who has ultimate responsibility for all firearms used as props, as well as to ensure the safety of the cast and crew.

- Dave Halls, who was the Assistant Director, had handled the gun. Allegedly, Gutierrez-Reed handed the gun to Halls, who handed it to Baldwin.

In addition, the shooting incident has sparked a debate about the general use of firearms as props in TV and movies.

I want to state unequivocally that I have no background in the film and theater industry, but I do have a level of knowledge and experience with many different kinds of firearms that exceeds at least 99% of the general public.

The purpose of this post is to review the facts of the incident (current, as of this writing), provide my analysis and thoughts about what may have led up to the incident, as well as what could and should have been done to prevent it.

Table of Contents

The Facts of the Incident

(as we currently know them)

- The gun in question is an Italian clone of a Colt Single-Action Army (SAA) chambered in .45 Long Colt (LC). Typical loads weigh 250 grains (7000 grains = 1 lb) with a muzzle velocity of about 800 feet per second (f/s or fps).

- Ms. Gutierrez-Reed (Armorer) allegedly handed the gun to Mr. Halls (Assistant Director) who allegedly handed the gun to Mr. Baldwin. At that time, Mr. Baldwin was allegedly told that it was a “cold” gun – meaning that there were supposed to be no live rounds in the gun.

- The director and cinematographer were obtaining a close-up shot of Mr. Baldwin pointing the gun directly at the camera while pulling the hammer back (cocking the gun).

- In an interview for the show, 20/20 (Ep 45.9, “The Deadly Take”, 12/10/2021), Mr. Baldwin states that the cinematographer, director, and himself were framing up the shot – figuring out the right position for the gun and the camera. As part of that process, Mr. Baldwin performed a dry run or practice run, where he cocked the pistol (pulled the hammer back) with his thumb.

- Mr. Baldwin states that he then released the hammer by removing his thumb, and that his finger was not on the trigger at any time.

- At that point, the hammer fell forward against the firing pin, and a live round was discharged.

- It’s unclear whether the bullet impacted the camera. As it continued in flight, the bullet traveled through the cinematographer’s chest, who was fatally wounded, and lodged in the director’s shoulder, who was injured but survived.

- One supplier provided both the gun in question, and the dummy (non-firing) rounds that were supposed to be loaded in it. The supplier has internal procedures to ensure that ONLY dummy rounds were shipped to the set.

As of this writing, the major question is how a live round ended up on the set, which is supposed to be expressly-prohibited.

The .45 LC Cartridge

The .45 Colt or .45 Long Colt cartridge was originally a black powder cartridge that dates back to the early 1870’s, to be used in the Colt SAA pistol.

Metal of that era was not as strong as modern steel, and as such, it was designed to operate at much lower chamber pressures than modern rounds fired from a modern firearm. Even though the cartridge is longer than its modern .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) counterpart, in terms of muzzle energy they are similar.

Muzzle energy, typically measured in foot-pounds (ft⋅lbs or ft-lbs) is the amount of kinetic energy a bullet has, as it exits the tip (or “muzzle”) of the barrel after having just been fired. Muzzle energy is an indication of the destructive force applied when a bullet strikes a target.

The formula for kinetic energy is:

EK = ½ ⋅ m ⋅ v2

The weight of a bullet is measured in “grains” (gr), where there are 7,000 grains per lb.

Further, the “pound” is a unit of weight, not mass. To get to mass, measured in slugs, we have to divide by the acceleration due to gravity, which is 32.2 ft/s2. 1 lb = 1/32.2 slugs.

If we plug all of this in, including the muzzle velocity (velocity as the bullet leaves the barrel) of the bullet,we get:

EK = ( w ⋅ v2 ) / ( 7000 ⋅ 32.2 ⋅ 2 )

EK = ( w ⋅ v2 ) / 450,800

- w = bullet weight in gr (grains)

- v = muzzle velocity in ft/s

Typical loads for the .45 LC are 250gr at around 750 ft/s:

EK (.45 LC) = ( 250 ⋅ 7502 ) / 450,800 = 140,625,000 / 450,800 = 312 ft⋅lbs

To put this in perspective, 312 ft⋅lbs is about 423 Watt-seconds, or about enough energy to power a 15 Watt LED lightbulb for about 28 seconds. This doesn’t seem like a lot, but bullets transfer their energy very quickly after they strike a target. If the bullet flew a total of about 8 feet during the shooting incident, then the total flight time would be about 0.0107 seconds, which equates to about 39,000 Watts of power, but only for a tiny fraction of a second!

Independent of muzzle energy, the mass of the bullet also determines how quickly it loses energy after it strikes a target, also known as “terminal effect” or “terminal ballistics”. .45 LC is a heavy bullet, which means that it has a lot of inertia, and maintains its energy after striking a target, which can lead to overpenetration. Overpenetration occurs when a bullet strikes its target, travels through the intended target, and then exits. When a bullet overpenetrates, it becomes airborne again, and can strike another target, which is exactly what happened.

Every cartridge usually has a few standard “loads”, which is the bullet weight and the amount of powder “loaded” in to the cartridge. With much older cartridges such as the .45 LC, there is often a much wider variety of loads, and fewer actual standards. From a practical perspective, this means that it’s difficult to tell what bullet load was fired during the incident.

For example, if you are shooting .45 ACP, and you go to the local sporting goods store and pick up a couple of boxes of the cheapest ammunition they have, you will most likely end up with 230gr “ball” (full metal jacket) with a muzzle velocity of about 850 ft/s (369 ft⋅lbs), because that is a very common load. The muzzle velocity can vary a bit, due to the fact that different ammunition manufacturers use different powders and testing procedures, but the weight of the bullet and the amount of powder is fairly standard. Another fairly standard .45 ACP load that you might find is 185gr hollow point at 1,000 ft/s. Even though you can purchase .45 ACP ammunition with a variety of bullet weights and muzzle velocities, if you picked a box off the shelf at random, it would most likely be either 230gr ball, or 185gr hollow point.

The same can’t be said for .45 LC. If you pick a box at random, you might get a box of 200gr at 700 ft/s, or 230gr at 700 ft/s or 165gr at 900 ft/s or 250gr at 800 ft/s etc.

Despite its large size, the .45 LC actually has much less muzzle energy than similar, but more modern cartridges. For example, comparing the .45 LC to the .44 (Remington) magnum developed in 1955, the .44 has the same case length, nearly the same diameter, and similar bullet weight, but operates at a much higher chamber pressure, resulting in a velocity of nearly 1,200 ft/s (about 50% faster) with a muzzle energy of around 740 ft⋅lbs – more than double.

Since we know with certainty that overpenetration did occur, because the same bullet traveled through the cinematographer and then in to the director, this would tend to indicate a heavier, faster load with slightly more muzzle energy. The .45 LC cartridge can go all the way up to about 450 ft⋅lbs.

The other major factor is bullet shape, and again, .45 LC ammunition comes in a wide variety of bullet shapes.

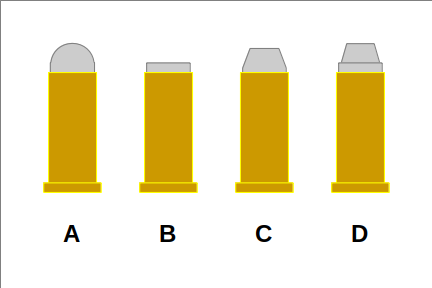

A: Lead Round Nose (LRN)

B: Wadcutter (W or WC)

C: Flat Nose or Truncated Nose

D: Semi-Wadcutter (SW or SWC)

- Lead Round-Nose (LRN) has straight sides and a round “ball” nose. This type of bullet flies the farthest and maintains velocity over longer distances, but is also more likely to overpenetrate when it hits a target.

- Wadcutter (W or WC) rounds are completely flat, and are designed for target shooting. The completely flat profile punches a clean hole in a paper target, and can easily be seen from a distance. Wadcutters are ballistically unstable, but aside from hollow points, have the greatest terminal performance – they tend to stop within the target rather than overpenetrate.

- Flat nose or truncated nose bullets have a slight taper that ends abruptly. These tend to be more ballistically-stable than wadcutters, yet still have a flat face that is somewhat useful for target shooting. This type of bullet is also good for hunting, because they are accurate, but tend to transfer a lot of energy in to the target rather than overpenetrate.

- Semi-wadcutter (SW or SWC) are like a cross between a wadcutter and a flat-nosed bullet. The center part of the face of the bullet is a truncated cone, but the base of the cone ends in a sharp shoulder. Like wadcutters, they are good for target practice, and like a truncated-nose bullet, they are ballistically-stable. Because of the small surface area of the conical section, they can be prone to overpenetrate in a manner similar to a round-nosed bullet.

- Hollow point (HP) bullets (not depicted) are like truncated-nosed bullets, but there is a recess in the face of the bullet, rather than being completely flat. The depth and shape of the recess varies by brand and manufacturer, but the purpose of the recess is to promote expansion or “blooming” once the bullet strikes its target, causing the bullet to dump its kinetic energy much faster. This increases the terminal effect while severely reducing the likelihood of overpenetration. Hollow point bullets are used primarily for self-defense and hunting.

With “Rust” being a western, Lead Round-Nose bullets would be the most historically-accurate.

However, from the pictures I’ve seen (and who knows if they are pictures of THE ACTUAL prop bullets), they seemed to be using Semi-Wadcutters, which weren’t even developed until the mid-1900’s.

In modern times, the .45 LC cartridge is used primarily for target shooting and action sports, although there are self-defense guns such as the Taurus Judge chambered in .45 LC. Also, being a much older cartridge, the .45 LC is not known for extreme accuracy, compared to similar but more modern cartridges like the .44 magnum. So, unlike common military, defensive, and hunting cartridges, if you were to grab a random box of .45 LC ammunition, it would most likely be truncated nose or semi-wadcutter, geared toward target shooting, and it’s actually quite difficult to find round-nose.

Considering the overpenetration that occurred, the live round was most likely a semi-wadcutter. Please note that this is only educated speculation. We can further speculate that the load was at the higher end – perhaps in the range of 250 grains, traveling at around 800 ft/s for a muzzle energy of 355 ft⋅lbs. Unfortunately, if the dummy rounds were also semi-wadcutters, there would be no external, visual cue to differentiate the two.

The Colt Single-Action Army (SAA) Revolver

Mr. Baldwin states that he thumbed the hammer back (cocking the gun), released the hammer, and the hammer then dropped, resulting in the gun firing. He states that his finger was never on the trigger.

Many gun experts have pointed out that a Colt-pattern SAA revolver is not capable of functioning in this manner.

The hammer has four positions:

- Lowered (default) position. Older revolvers have a fixed firing pin, but modern revolvers use a transfer bar. In a transfer bar system, the firing pin does not normally align to the primer of the cartridge. Only when the trigger is pulled, a nub on the back of the trigger engages the transfer bar, which forces the firing pin in to correct alignment. The effect of this system is that the revolver is made automatically safe when the hammer is lowered, unless the trigger is also being pulled. Even if the gun is dropped with the hammer over a live round, it won’t fire.

- Safety cock – pulling the hammer back just a short distance locks the hammer, which can’t be released by pulling the trigger. The purpose of this position is to prevent the firing pin from contacting the primer of a live round, even if dropped.

- Half-cock – pulling the hammer back one more click locks the hammer at half-cock, and releases the cylinder lock. In this position, the cylinder is free to rotate, which is how you load and unload the gun. Pulling the trigger does not release the hammer.

- Full-cock – pulling the hammer fully-backward advances the cylinder, and locks the hammer back. In this position, the gun is ready to fire, by pulling the trigger.

Gun experts are quick to point out that if his finger was not on the trigger at the time the hammer dropped, there is no way the gun could have fired.

- If the hammer wasn’t quite at full-cock when he released it, it should have stopped at the half-cock or safety cock positions unless the trigger was being pulled at the time.

- If, somehow, the hammer made it all the way down, the firing pin should have been out of position unless the transfer bar was tensioned by the trigger.

However, the practical reality isn’t that simple.

The gun itself was rented. Who knows what condition the gun was in – it might have been well-maintained, or it might be worn out. Who knows if the transfer bar even functions correctly, or if it even has a transfer bar. Who knows if the lockwork is worn or dirty. It could have been fired a few times, or 50,000 times.

Likewise, if you’ve ever been to a gun show, you’ve probably handled a gun, way off to the side, on one of the dimly-lit tables, that has loose parts and rattles when you shake it, because it’s completely worn out.

A firearm in good condition should have a tight “lock-up”, meaning that all parts fit snugly, and mechanical parts such as the cylinder, hammer, and trigger all lock tightly. With the hammer down, nothing should be loose, and nothing should rattle.

It’s not difficult to imagine that if a gun is to be primarily used as a prop, it might not be in tip-top mechanical condition.

It’s not inconceivable that the lockwork was worn enough to prevent the hammer from stopping at the half-cock or safety positions. It’s also feasible that the transfer bar might be jammed, or that it might not even have a transfer bar (solid firing pin).

I’m no psychologist, but it’s also possible that Mr. Baldwin is misremembering the position of his trigger finger due to the trauma of the event, or that he is psychologically-repressing the memory of the event due to guilt. As he stated in the interview, he has handled firearms in the past, and knew better than to have his finger on the trigger.

Dummies, Blanks, and Live Rounds

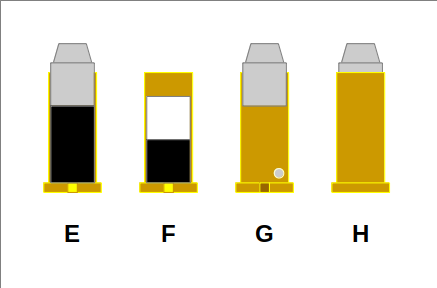

E – Normal “Live” Round

F – Blank Round

G – Dummy Round

H – Externally, Live rounds and Dummy rounds look nearly identical.

- A normal, “live” round has a primer, a full powder charge, and a bullet that is pressed or crimped in to the shell case. When the firing pin hits the primer, the primer ignites the powder charge, propelling the bullet with tremendous force through the barrel.

- A blank round has a primer, a reduced powder charge, and paper wadding instead of a bullet. When fired, you get a loud noise, a muzzle flash, and a puff of smoke, as if a live round had been fired. The paper wadding partially burns, or is shredded and expelled out the front of the barrel.

- A “dummy” round has no primer or a fired primer, and no powder. A bullet is seated or crimped in the case, as if it were a normal round, but the round is incapable of being fired. A “BB” or ball bearing is sealed in the case. The procedure used to distinguish a dummy round from a live round is to shake it – if the cartridge rattles, it’s a dummy round.

Other than perhaps a missing or fired primer, there is no way to externally, visually distinguish a live round from a dummy round, and they would weigh about the same as well.

Although the BB rattles when a dummy round is shaken, the only way to guaranty with certainty that a cartridge can’t be fired is to point the gun in a safe direction, load the round in question, and attempt to fire it.

A Few Words on Blank Rounds

Visually, a blank round is easy to identify, because it doesn’t have a bullet protruding from the front of the cartridge.

Because blank rounds don’t employ a bullet that would normally become a projectile when fired, people tend to think of them as “safe”, but blank rounds are far from safe.

- At close range, the burning paper wadding can cause burns, bruises, or even cause trauma to soft tissue such as the eyes.

- At extremely close or contact range, the paper wadding can hit with enough force to act like a bullet, penetrating tissue and causing severe injury or death.

- Setting aside the wadding, a cartridge is a small bomb. At contact ranges, even the hot, high-pressure gas can cause severe burns and trauma.

- If there is any kind of barrel obstruction, the gas pressure of a blank round can cause it to become a projectile. This is exactly what happened to Brandon Lee in 1993 while filming “The Crow”.

Because of these factors, blank rounds have to be treated essentially like live rounds, especially at close ranges, and all normal gun safety protocols must be applied.

Anatomy of an Accident

As they say about a plane crash, there does not seem to be one, single failure. Rather, it seems like the incident resulted from a string, or series of failures and poor decisions.

- Live rounds should not be allowed anywhere near the set, but somehow at least one live round not only ended up on the set, but made its way in to a real firearm.

- Three people handled the gun without checking it properly. If any of the three of them had checked it properly and thoroughly, the chances of an accident would have been severely reduced.

- Safety protocols weren’t followed. After the Brandon Lee shooting incident in 1993, certain safety protocols were mandated by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. Clearly, the following safety protocols were not followed:

- Firearms must be checked before and after each take

- Loaded guns must never be pointed at anyone

- If firearms are to be fired directly at the camera, a plexiglass shield must be erected

- Only the person certified for the weapon or someone under their direct supervision may hand a weapon to an actor

- The following general gun-safety protocols were not followed:

- Always assume a gun is loaded until you check it personally

- Always point the gun in a safe direction.

- When firing, be aware of who or what is within your field of fire, and always ensure that you have a proper back-stop.

- Keep your finger off the trigger unless firing.

- Prior to the incident itself, there had been numerous complaints about safety, especially firearm safety, and two negligent discharges had already occurred.

- Few firearm safety briefings had been conducted.

Other factors that may have been at play, but it’s hard to tell what is fact vs. rumor:

- The assistant director, Mr. Halls, has had numerous, previous complaints about firearm safety, and safety in general

- The “Rust” filming was only the second time Ms. Gutierrez-Reed had worked as lead armorer. There were numerous complaints about firearm safety, and in particular, complaints about how she handled firearms on both the “Rust” set, and on her previous job.

It’s clear that there seems to have been a systemic attitude of carelessness and lax safety standards regarding the firearms. As the safety breaches continued to pile up, this ultimately led to a situation that was ripe with danger.

- None of the three people involved performed a thorough check of the firearm before it was discharged. Each person involved just assumed that someone else either had checked it or would check it, or even worse, that because ti had been checked at some point previously, that it was still “OK”.

- The gun, “cold” or not, should never have been pointed at another person.

- If a plexiglass shield had been used, two casualties most likely could have been prevented.

- There were two negligent discharges prior to the shooting incident – a clear indicator of lax safety standards

After the first negligent discharge, all filming should have been halted for at least 24 hours in order to conduct a top-to-bottom safety review, and quite frankly, someone probably should have been fired at that point.

The big question, of course, is where did the live round come from?

Quick Note on the 1993 Brandon Lee Shooting Incident

The “Rust” shooting incident has been heavily compared to the 1993 Brandon Lee shooting incident.

1 – The crew made “dummy” rounds from live rounds by removing the powder and replacing the bullet at the tip of the cartridge.

2 – The “dummy” round still had a live primer

3 – When fired, the live primer in the “dummy” round had enough force to lodge the bullet inside the barrel

4 – The “dummy” cartridge was removed and replaced with a blank round. The bullet from the dummy round, together with the powder charge from the blank round acted as a live round.In that incident, the crew made their own dummy rounds by removing the powder charge from live rounds, neglecting the primer, which could still be fired.

At some point, one of these rounds was fired, resulting in the bullet separating from the dummy round, and becoming lodged in the barrel.

Blank rounds were subsequently loaded in to the same gun for an action scene. When fired, the bullet from the dummy round became a projectile, striking and killing Brandon Lee.

Where Did the Live Round Come From?

That’s the big question. Several theories abound, so none of this is taken as fact.

The Prop Company

The live round might have been supplied by the prop company, intermixed with a box of dummy rounds.

The prop company has stated that they have internal procedures to prevent this from happening, and two people independently verify each dummy round (using the rattle test) before it goes out the door.

At this point, there is no reason to disbelieve any part of this statement.

However, let’s speculate for a moment. If the prop company did somehow supply a live round, it would therefore be due to an internal control failure. This would most likely have happened in the past, as well, and it’s easy to imagine that the prop company would gain a poor reputation for safety. That’s not the case.

Further, even if the prop company did supply a live round by accident, this should have been caught by the armorer.

In theory, the first thing the armorer should have done after receiving the ammunition would have been to go through every round and verify that each was in fact a dummy round. Any live rounds or suspect rounds should have been immediately discarded (or ideally, destroyed).

Sabotage

There was a labor dispute immediately prior to the shooting incident, resulting in most of the crew walking off the job. In addition to wages and accommodations, the crew cited safety concerns.

There has been speculation that one of the disgruntled crew members may have surreptitiously replaced one or more of the dummy rounds with live rounds.

This is just speculation, and can’t be verified.

If this did occur, how did someone gain access to guns and ammunition that should have been kept secured (locked away) when not in use?

If the guns were secured, but sabotage did occur, this should have been caught by the armorer because the guns and ammunition should have been inspected before use.

The armorer should have both taken steps to prevent tampering, and detected any potential tampering before the gun was handed off.

Plinking

When most of the crew walked off the set, this apparently introduced some long delays.

It’s rumored that during the delay, some of the remaining crew took the prop guns and used real ammunition to do some “plinking”, which is basically just shooting at cans or other informal shooting.

It is implied that a live round was left in the gun after the crew was done plinking.

Again, we don’t know if any of this is fact, but let’s just assume that it’s true – the crew took guns from the set, spent time repeatedly shooting them, loading live ammunition multiple times, after which the guns were returned to wherever they had been originally stored.

There are some problems with this scenario.

- The guns should have been physically-secured – locked up – when not in direct supervision of the armorer.

- If you’re out in the middle of the desert, and you decide that you want to do some plinking with the guns that are already there, where do you get live ammo? There were supposed to be no live rounds on set, and it was expressed that the set was “a couple of hours” outside of town. So, you drive two hours to the hardware or sporting goods store, and then two hours back, just so that you can pop off a few rounds? This seems highly unlikely.

- When the guns were returned, they should have been unloaded, since no live rounds are allowed on the set, but let’s just say that someone irresponsibly left a loaded gun sitting around. Then it would have fallen to the armorer to check and clear the gun before loading it with dummy rounds for the next scene.

This entire scenario sounds completely implausible, but if these events did occur, any live rounds left in the gun should have been found by the armorer and discarded. Further, the armorer should have secured the guns to begin with, so that they could not have been used in this manner.

One of the Crew Brought A Box of Live Ammunition

As .45 LC is not a popular cartridge, it’s very unlikely that someone just happened to have a random box of .45 LC ammunition in their car.

The more likely scenario is that there had been at least one box of live ammunition on the set the entire time – either the armorer or someone else familiar with the guns brought the ammunition to the set, and somehow a live round got intermixed with dummy rounds.

There have been multiple interviews with other directors and other armorers who have stated that no live ammunition should ever be allowed on the set, for any reason, at any time. Further, it has been stated that this would be grounds for immediate dismissal.

As mentioned, the armorer should have unloaded the gun and double checked all of the rounds being used for the next scene.

Common Theme

The common theme to all of these scenarios is that the armorer should have unloaded and checked the gun before the next scene.

If the gun had been unloaded and checked, the live round most likely would have been discovered.

Ultimately, the armorer is responsible for both the guns and the ammunition used on set.

Recommendations for Additional Safety Procedures

There are three types of guns that can be employed as a prop:

- Rubber, non-functional guns, which can’t be loaded, can’t be fired, and are completely safe.

- Functional replicas, which mimic the functionality of a gun without being able to actually fire.

- Blank-firing guns, which are completely functional.

Functional replicas are often made of cheaper metal, and don’t have a firing pin, nor the ability to be converted in to a firearm by adding one – for example, there might not be a slot for a firing pin. Functional replicas exist for just about every type of firearm, and mimic the mechanical functionality, including all user controls. For example, you can cock the hammer, or rack the slide, but the replica can’t really fire a live round. Most replicas are designed to prevent live ammunition from being loaded, but some of them even come with dummy rounds that can be loaded and unloaded as if they were real cartridges.

In a situation where a visually-similar replica doesn’t exist, a real gun can be made non-firing by removing the firing pin.

If the gun in question had been a replica or a non-firing conversion, then the live round would be a non-issue.

Blank-firing guns are real, fully-functional firearms. In some cases, a gun must be modified so that it cycles properly, because blank rounds don’t produce enough gas pressure to cycle a semi or fully-automatic weapon.

A “blank adapter” fits on the end of the barrel, and produces enough pressure from a blank round so that the action cycles. Blank adapters can be external, or they can be welded in to the barrel. A small hole in the adapter allows for muzzle flash and a puff of smoke when a blank round is fired, and allows the burning wadding to egress the barrel.

Firing a full-power load with a real bullet in a gun fitted with a blank adapter would be catastrophic – the gun would explode. Therefore most blank-firing guns have been modified such that a real, full-power cartridge can’t be loaded. This can be accomplished by changing the head-spacing, so that the gun can’t come in to battery if a real cartridge is loaded. However, when loaded with slightly-shorter blank rounds, the gun would continue to fire and function normally.

Because bullet impacts and other artifacts are accomplished with special effects, there isn’t a scenario where a real firearm can’t be substituted with a blank-firing conversion.

Additionally, all rounds should be marked or painted so that they are clearly, visually identifiable as a “dummy” (non-firing) vs. blank round.

This could be accomplished by painting a stripe on the case of dummy rounds, or stamping the base with a specific stamp.

Additionally, non-firing guns should be marked, and ONLY used with dummy rounds, while blank-firing guns should be marked differently, and NEVER used with dummy rounds. This could be as simple as a green or red stripe on the base of the gun, or an extra stamp on the barrel.

It’s clear from all accounts of the incident that the guns were not adequately secured, and this seems to have been normal practice. From what I’ve read, the industry-acceptable practice is to secure every firearm, even non-firing ones, all the time. All guns and ammunition should be stored in a locked cage, and blank-firing guns should be stored in a separate locking cage or cabinet.

- The guns can’t be tampered if they are kept secured at all times

- Markings or color-coding on the guns ensures that the right type of gun is used for each scene

- Markings or color-coded ammunition ensures that ONLY the proper type of ammunition is used for each gun

And of course, normal gun safety practices apply –

- Assume every gun is loaded until you inspect it personally

- Keep the gun pointed in a safe direction

- Keep your finger off the trigger

- Always be aware of your backstop and potential targets within your field of fire

- Keep the gun holstered or in a locked case when not in use

As do industry safety practices such as using plexiglass shields, checking every gun before and after every take, and cleaning and inspecting every gun, every day.

Conclusion

After the “Rust” shooting incident, many people are calling for a ban on using real guns as movie props.

That assertion could only be made by people who are uneducated about firearms and firearm safety.

“The Matrix” (1999) was notable for multiple, extensive shoot-out scenes using a variety of firearms, including fully-automatic machineguns and submachineguns. There were around 80,000 blank rounds fired during the filming, of which about 2,000 appear on-screen. Excluding non-functional prop guns and non-firing replicas, there were probably close to 200 actual firearms on the set, each capable of firing blank rounds. In the two decades since it was made, there has never been any report of firearm safety issues during the filming. No mistakes, no “accidental discharges”, and no injuries.

This proves that when done correctly, movies can be safely made using real firearms.

Conversely, I’m sure people are injured or killed by cars while filming TV and movies, but we aren’t calling for all cars to be props.

Using real guns in movies adds a level of realism and believability that can’t be achieved with rubber guns.

However, the TV and Movie industry should make better use of existing technologies:

- Non-firing replicas or conversions can be used for most scenes

- Dedicated blank-firing conversions can be used for shooting scenes

Although there is no reason to use a fully-functional firearm as a movie prop, there is no need to ban guns completely.