Previously, I’ve written about gun-related movie myths in “Movie Myths: Guns – Part 1“, and in there, I described in detail how guns work – both automatics and revolvers.

Since that time, I’ve thought about making a state diagram that helps explain some of the common gun-related continuity errors that you regularly see in movies and TV.

The result is the diagram that you will see in this article, along with a higher-resolution PNG and PDF that you can download for free, which would make a nice wall decoration for any gun enthusiast.

Download the PDF here, or the PNG here.

Read on for more information about state diagrams and gun-related movie continuity errors…

Table of Contents

Quick Recap

Let’s review a few things before we dive in to the diagram.

What the Heck is a State Diagram?

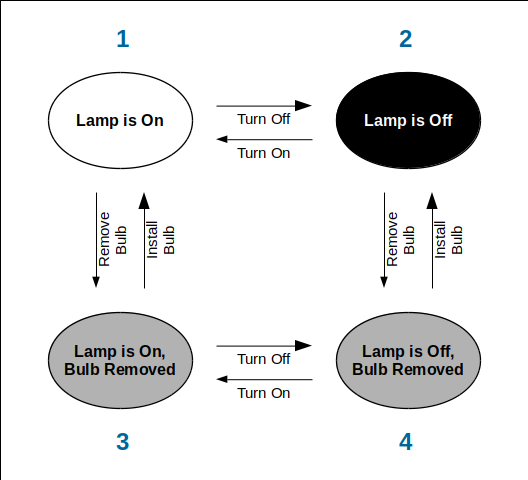

Technically called a state-transition diagram, it shows all possible states of a device (logical or physical), and how the device moves from one state to another.

For example, if you turn on a lamp, its state is “on”. It can’t be turned “on” while it’s on, but it can be turned “off”. If you remove the bulb, the rules governing the state changes are still in effect, despite the fact that the state is effectively hidden.

In states 1 and 3, the lamp is on. In states 2 and 4, the lamp is off. However, in states 3 and 4, the state is effectively hidden, but the rules for state changes are still in effect.

If you start at state 1, the bulb is lit. If you turn the lamp off, you transition to state 2. By removing the bulb, you transition to state 4. If someone else were to walk up to the lamp at this point, they would see that the bulb is removed, but they wouldn’t know if the lamp is in state 3 or 4. This is known as a hidden state. If you reinstall the bulb, the state becomes obvious (or the bulb is burned out).

A state diagram is a model for how the lamp works. It can’t, for example, go from state 4 to 1 without passing through states 2 or 3. If you see someone in a movie turn off a lamp and remove the bulb, in your mind, you know the lamp is in state 4. If the hero comes along a few minutes later, and lights the lamp simply by screwing in the bulb, you intuitively know that this can’t happen. The hero broke the “rules of the lamp”, and this is distracting to the viewer.

A handgun is a little bit more complicated, which is why you often see gun-related continuity errors in TV and movies, and rarely see lamp-related continuity errors.

Like a lamp, guns have hidden states. Unlike a lamp, a gun has many more states that are interconnected with a much more complex set of rules. When a gun enthusiast watches a movie or TV show in which a handgun fails to follow these rules, it can be distracting.

A state diagram helps reduce continuity errors by providing a set of rules that determine what actions are valid for each state. For example, you can’t fire a gun unless it’s chambered, or perhaps less obvious, you can’t fire a single-action handgun unless you cock the hammer.

Quick Recap: Semi vs Fully Automatic

As I previously discussed in Gun Myths, the term “automatic” doesn’t necessarily mean “fully-automatic”. It means that the gun “automatically” loads the next round when fired. In review:

- Semi-Automatic (Semi-Auto): The gun fires one round when the trigger is pulled. The next round is loaded automatically, but the gun does not fire again until the trigger is released and then pulled again.

- Fully-Automatic (Full-Auto): The gun fires, and then continues to load and fire subsequent rounds until the shooter releases the trigger.

The vast majority of “automatic” handguns are semi-automatic, and that’s what we will be focusing on.

Quick Recap: Single Action vs Double Action vs Double Action Only

Single action (SA) means that the hammer must be manually cocked in order for the gun to fire. Firing cycles the slide, which cocks the hammer, so this only needs to be done manually for the first shot. After that, the gun is always ready to fire after each shot, until the magazine runs out of bullets.

- No single-action gun can be fired if the hammer is not cocked. The shooter must manually cock the hammer and then pull the trigger.

- The two most notable types of single-action, semi-automatic guns include 1911s (plus clones and variants), and Desert Eagles.

Double action (DA) means that the gun can be fired uncocked (with the hammer down). Pulling the trigger forces the hammer backward, until it reaches the cocked position, at which point the hammer drops and the gun fires. This all happens with one smooth motion, referred to as a “long” trigger pull.

Most double-action handguns can be fired as if they are single-action by manually cocking the hammer. This is also the default state after the first round is fired, and the slide cycles. Firing with the hammer cocked is known as a “short” trigger pull.

- Double-action handguns can be fired with the hammer cocked (short trigger pull) or lowered (long trigger pull)

- Some handguns are Double-Action Only (DAO), which means that the gun lacks a single-action mode. The hammer fully lowers after each round is fired, requiring a long trigger pull to fire the next round.

- Smith & Wesson, HK, Baretta, and SIG are generally double-action, as are most Walther / Makarov clones and variants.

Similar to DAO, striker-fired handguns use a captive spring-loaded firing pin (called a striker) to impact and thus ignite the primer of each cartridge. Made hugely popular by Glock in the 90’s, now many major manufacturers offer striker-fired models:

- Glock (all models)

- SIG P320

- HK VP9. Interestingly, the HK VP70, which was designed in the late 1960’s and produced as early as 1970, is one of the first “modern” striker-fired pistol designs.

- Smith & Wesson M&P Series

- Springfield Armory XD Series

Generally, striker-fired handguns can be treated as DAO with respect to state and state-transition rules.

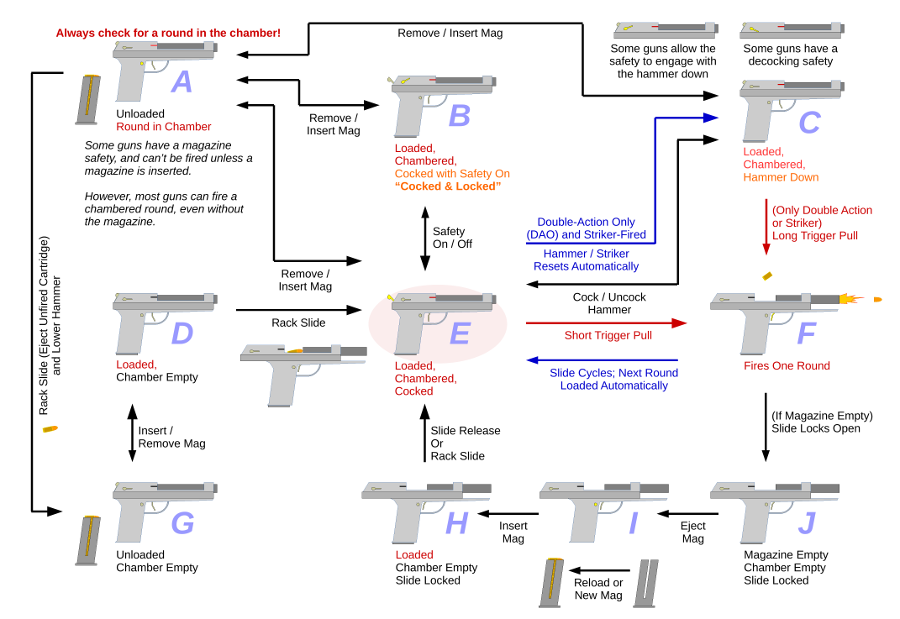

Handgun State Diagram (Automatic)

States and Transitions

| State | Description | Transitions |

|---|---|---|

| A | Magazine Unloaded, Round in Chamber

Although some guns have what’s known as a magazine safety that prevents the gun from being fired when the magazine is removed, most do not. This makes state A the most dangerous one – people often remove the magazine without checking the chamber, not realizing that the gun can still be fired. When unloading an automatic, always remove the magazine first, then check the chamber.

|

Insert Mag (cocked): E

Insert Mag (cocked + safety): B Insert Mag (hammer down): C Rack the Slide: G |

| B | Loaded, Chambered, Cocked with Safety On

Called “Cocked and Locked”, state B offers the greatest state of readiness without actually being able to fire. Because the hammer is cocked and under spring tension, carrying a gun in this state is only considered acceptable for people who have the proper training and experience. Critics argue that the handgun operator could accidentally bump the safety off, leaving the gun in an unsafe state. Proponents argue that it’s fast and accurate: Pull the gun, sweep the safety off as you aim, pull the trigger (pull, sweep, fire).

|

Remove the Mag: A

Disengage the Safety: E |

| C | Loaded, Chambered, Hammer Down

A Single Action (SA) handgun can’t be fired in this state. The operator must cock the hammer before it can be fired. Some SA handguns allow the operator to engage the safety with the hammer down, while others do not. Although a Double Action (DA / DAO) handgun can be fired in this state, it’s considered safer to carry than cocked and locked for two reasons:

Most DA handguns allow the operator to engage the safety in this state, further improving the safety factor when carrying.

|

Remove the Mag: A

Cock the Hammer: E Pull the Trigger (Safety disengaged): F |

| D | Magazine Loaded, Chamber Empty

Racking the slide chambers a round, making the gun ready to fire. This is considered the safest way to carry a handgun, but requires the most amount of manual effort to draw and fire, and requires the use of two hands.

|

Remove the Mag: G

Rack the Slide: E |

| E | Loaded, Chambered, Hammer Cocked (Ready to Fire)

Some Double Action (DA / DAO) handguns have a decocker, which safely lowers the hammer while relieving spring tension. Some decockers are built in to the safety (called a “hammer-drop safety” or “decocking safety”) while others are a separate lever, usually mounted in the frame near the trigger. To manually decock a Single Action handgun or a Double Action without a decocker, point the gun in a safe direction, put the thumb of your shooting hand over the hammer (applying tension), and pull the trigger. This releases the hammer, which you can then carefully lower by reducing the pressure of your thumb against the hammer. A Double Action Only (DAO) handgun immediately moves to state C. Firing a DA with the hammer cocked is known as a “short” trigger pull.

|

Remove the Mag: A

Engage the Safety: B Lower the Hammer: E Pull the Trigger: F DAO: C |

| F | FIRING

In this state, the hammer drops and hits the firing pin, which impacts the primer. Each cartridge (or “round”) contains a primer, powder, and bullet. The primer ignites the powder, pushing the bullet through the barrel of the gun with great force and therefore, at great velocity. When an automatic handgun is fired, the slide is forced backward, usually in one of three ways:

When the slide cycles, several things happen in rapid succession.

If the gun is fully-automatic, and assuming the trigger is still being pulled, the hammer would drop as soon as the seer is released, causing the next round to fire automatically, and this will continue until the magazine is empty. If the gun is semi-automatic, the trigger stays disconnected until the shooter releases it. Pulling the trigger again fires the next round. If there are no more bullets left in the magazine, most guns lock the slide open, and the gun must be reloaded before it can be fired again.

|

Mag NOT Empty (DA / SA): E

Mag NOT Empty (DAO): E then immediately C Empty Mag: J |

| G | Unloaded (Magazine Removed), Chamber Empty

Properly unloading a handgun involves removing the magazine, making sure that the chamber is empty (by racking the slide), and releasing spring tension on the hammer by decocking. This is the best state for storing a handgun.

|

Insert Mag: D |

| H, I, J | Reloading

When the last round is fired, a tab on the magazine’s follower engages the slide lock, causing the slide to lock open (J). Reloading consists of removing the empty magazine, and inserting a loaded one (I). To make the gun ready to fire, the shooter releases the slide using the slide release, or with a slight rearward pull of the slide (H).

|

J – Eject Mag: I

I – Insert Mag: H I – Remove Mag: J H – Release Slide: E |

States D, G, H, I, and J are all more or less “safe”, with the chamber empty, and states A, B, C, and E are more or less “ready to fire” with a round in the chamber.

Most people store a handgun in state G, with no magazine loaded and the chamber empty. Inserting a magazine moves the gun to state D, but the chamber is still empty.

For home defense, you might keep a handgun in state D stored in a lock box or safe near your bed or in your bedroom closet.

From state D, racking the slide loads a round from the magazine in to the chamber, and the gun is ready to fire in state E. “Racking” or cycling the slide involves pulling the slide fully-rearward and then briskly releasing it, which allows the slide to spring forward, loading a round from the magazine in to the chamber as it goes.

Pulling the trigger (short trigger pull), of course, fires the gun (F). If there are additional rounds in the magazine, the slide cycles, loading the next round from the magazine in to the chamber, returning to state E, which is ready to be fired again.

If the magazine is empty when fired, the gun goes from state F to J, where the slide locks back. The shooter then ejects the empty magazine using the magazine release (I), loads a new magazine (H), and from here, returns to state E (ready to fire) by either pressing the slide release (usually on the left side) or by partially-racking the slide. Since the slide is already locked back in state H, only a slight rearward motion is required, which releases the slide lock. Letting go of the slide then causes it to spring forward, loading a round from the magazine in to the chamber.

From state E (ready to fire), there are two “quasi-safe” states:

- State B is called “cocked and locked”, where the gun is loaded, chambered, and the hammer is cocked, but the safety is engaged. Some double-action guns allow this state, while others do not. Disengaging the safety returns the gun to state E (ready to fire).

- In state C, the magazine is loaded, a round is chambered, but the hammer is lowered.

- For a single-action handgun, this renders it unable to fire. A single-action handgun must be manually cocked, returning it to state E before it can be fired.

- A double-action or striker-fired handgun may be fired with a long trigger pull, which makes state C slightly safer than state E.

A Double-Action Only (DAO) or striker-fired gun, when fired (state F), basically transitions through state E then directly to C, where the slide cycles and a new round is loaded (E), but then the hammer or striker is reset to an uncocked position (C). Each round fired from a DAO or striker handgun requires a long trigger pull.

And last, but not least, to unload the handgun, the shooter first removes the magazine, transitioning from states B, C, or E to state A. At this point, there is still a round in the chamber, which can be a very dangerous situation. Because states A and G look very similar, it’s easy to forget that the gun could still fire. Some guns have what is called a “magazine safety” that prevents this, but most do not – they are capable of firing without a magazine inserted, which takes the gun from state A through F to G. However, this should not be considered a standard operation. To finish unloading from state A, racking the slide ejects the unfired cartridge, and takes the gun to state G, and the final step is to release spring tension on the hammer by decocking (not shown on the diagram).

A Few Words on Gun Safety

Safe Handling

State A (round chambered but magazine unloaded) is the most dangerous state. When people inadvertently injure themselves or others with a handgun, it’s most often because they forget to remove the last round from the chamber.

This is why you should always assume that every gun is loaded, and make it a habit to manually check the chamber whenever you pick up a gun, or especially when someone hands you one. To check the chamber, move the slide rearward about a half-inch, which is enough to see the brass cartridge case if a round is chambered, or the mouth of the barrel if not.

Because A and G look so similar, most guns have what’s called a “round in chamber” indicator, which is usually a red pin, tab, or bar that protrudes slightly when a round is present in the chamber, but the appearance can vary widely. This allows the shooter to readily determine the state of the gun, and some guns even have an indicator that protrudes enough to be felt in the dark, if the shooter runs a fingertip down the slide.

When you pick up a gun, or someone hands you a gun, ALWAYS:

- Keep your finger off the trigger

- Keep the muzzle pointed in a safe direction – usually up or down, but not pointed toward anything that bleeds, could get damaged, or cause the bullet to ricochet

- Check the round-in-chamber indicator, or pull the slide back about a half-inch in order to visually inspect the chamber, to make sure the weapon is unloaded

Never point a gun at yourself or anyone else, even as a joke, even if you think the gun is in a safe state.

Never put your finger on the trigger until the gun is aimed at a target and you intend to shoot.

Safe Carrying

You should never carry a gun in state E, because it is in its most ready state. Just a slight pressure against the trigger will cause it to fire. Even though most modern guns have ample safety features specifically-designed to prevent an accidental discharge, it’s more about the shooter’s awareness and experience. Also, older, cheaper, or worn firearms might not have these safety features, and could be subject to an accidental discharge, even if holstered. It’s just not safe to carry a gun in this state.

If you carry a gun, you need to make the best choice which balances between readiness and safety.

- For DAO, double-action, and striker-fired guns in state C, the gun is ready to fire, but requires a long trigger pull. This is the default mode for these types of guns, and is considered “safe” as long as the shooter is trained NOT to grab the trigger, and as long as the gun is carried in a holster which covers the trigger.

- For single-action handguns, state C effectively prevents the gun from being readily fired, because the hammer must be manually cocked in order to move the gun to state E. Modern guns prevent the hammer from contacting the firing pin when lowered, or have a half-cock setting. If the gun lacks such a safety mechanism, it should be carried chamber-empty.

- In state B (“cocked and locked”), the gun is ready to fire, but the safety is engaged. This requires the shooter to draw the gun, and then click the safety off before it can be fired. Critics of this mode make the argument that state B isn’t necessarily safe because the hammer is under spring tension, and because of this, the shooter, with the gun holstered, could accidentally disengage the safety. For example, if the holstered gun accidentally knocks against a piece of furniture, the exposed safety could become disengaged, leaving the gun in state E, at which point the gun is no longer safe to carry. If you carry a gun cocked and locked, you should have a holster that either covers or protects the safety so that it can’t accidentally become disengaged.

- In state D, the chamber is empty, requiring the shooter to first draw the gun from its holster, and then manually rack the slide in order to load a round from the magazine in to the chamber, before it can be fired. This is the safest state in which to carry a gun, but the least ready, as it generally requires two hands to chamber a round.

Safe Storage

For normal storage, any gun should be kept in its safest possible state:

- Magazine removed from the gun

- Chamber empty

- Decocked – If you store a gun long-term with the hammer cocked, the spring could be damaged

In addition:

- Magazines should be unloaded (ammunition removed)

- Guns and ammunition should be stored separately, each in a locked case, cabinet, safe, or drawer.

Optionally, guns can be partially-disassembled for the highest level of safety. For example, removing the slide from a handgun, or the bolt from a rifle prevents it from being fired unless the operator knows how to reassemble it first.

For home defense, a handgun needs to be stored in a more ready state – D or G (preferably state D, with a loaded magazine inserted) inside a sturdy, secure handgun lock box that’s lag-bolted in to a wall or floor. Do some research before you buy a handgun lock box – many, including some expensive models, are embarrassingly easy to bypass with simple tools, or by removing the hinge pin. Pro-tip: Keep at least one extra mag and a flashlight inside your handgun lock box.

Common Continuity Errors

Now that we’ve explained how the state diagram works, let’s explore how it can help us address some common continuity errors.

Error: Unloaded, But Not Unloaded

Tragically, and way too frequently, people accidentally shoot themselves or someone else because they confuse state A for state G. After removing the magazine, the shooter assumes that the gun is unloaded and therefore safe, forgetting that most guns can still discharge a chambered round, even without a magazine inserted.

Likewise, you often see this mistake in movies and TV, where someone removes the magazine, and then assumes that the gun is “safe”.

Error: Loaded, But Not Loaded

The opposite error is to assume that a gun is ready to shoot after simply inserting a magazine, where the shooter has confused state D with state E, which is a common movie mistake.

A very similar mistake that you often see in movies is when the good guy runs out of bullets, and the slide locks back (J). He ejects the magazine (I), and the camera cuts to him grabbing a new one. As he inserts it, the camera cuts back to his gun, which is now somehow in state G, so that when he inserts it, the gun moves to state D – quite incapable of being fired because the chamber is still empty. Yet, he immediately resumes firing at the bad guy without racking the slide first.

Error: Firing Single Action, Uncocked

A single action handgun in state C can’t be fired, unless you cock the hammer first, taking the gun to state E.

Error: Cocking the Hammer Menacingly

In this scene, the good guy points his gun at the bad guy, and threatens him. The bad guy says, “you don’t really mean it”, at which point the good guy cocks the hammer.

Let’s break this down a bit.

There are two scenarios:

- The gun is single-action, in which case the gun was perfectly safe to begin with, because a single-action handgun must be cocked (C to E) before it can be fired. If this was the case, the bad guy wasn’t actually being threatened until the good guy cocked the hammer, making the original gun-pointing-gesture meaningless.

- The gun is double-action, in which case the gun would have fired cocked or uncocked. Although cocking the hammer might have some dramatic effect, it essentially has no function.

Error: Racking the Slide Menacingly

Same scene as above, but instead of cocking the hammer menacingly, the good guy, with his gun pointed at the bad guy, racks the slide menacingly.

Again, there are two scenarios:

- The gun wasn’t chambered, in which case the good guy had been pointing an empty weapon.

- The gun WAS chambered, in which case the good guy just ejected an unfired round, which is pointless, and rather comical.

A slight variation, sometimes you’ll hear the sound of the slide being racked as the good guy (or bad guy) pulls his gun from its holster, but we don’t actually see him rack the slide. This happens because the sound effect person doesn’t know how guns work.

Conclusion

Please download, print, and enjoy the handgun state diagram.

Download the PDF here, or the PNG here.

The next time you watch an action movie, watch closely for continuity errors!